Publishing’s most legendary svengali wrote this work of science fiction in 1911. Is it a good? No. Is it “so bad it’s good”? No. Is it interesting from a historical perspective? Yes.

Publishing’s most legendary svengali wrote this work of science fiction in 1911. Is it a good? No. Is it “so bad it’s good”? No. Is it interesting from a historical perspective? Yes.

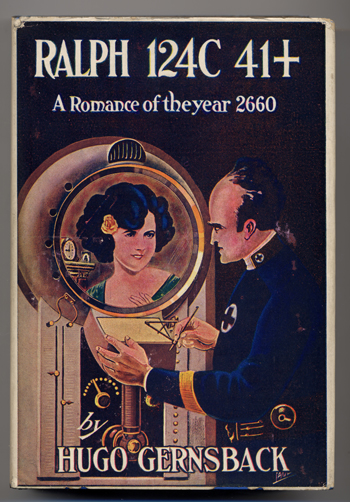

The story could be reduced to a boring paragraph, and an (only vaguely) interesting sentence: Ralph (a brilliant inventor) must rescue a charming moll from the clutches of a Martian. The book sometimes has the subtitle “A Romance of the Year 2660”, which is more fitting, because the it’s actually the year 2660 that’s the star, not Ralph. We get taken from place to place, Gernsback showing us all sorts of fancy toys and tricks, while the plot dodders along behind like a guest that isn’t sure he’s wanted at a party.

Science fiction vide Jules Verne (and Mary Shelley) uses futuristic technology to reveal truths about the human condition. Science fiction vide HG Wells uses futuristic technology to reveal truths about society and its ordering. Science fiction vide Gernsback uses futuristic technology to reveal truths about…futuristic technology.

He shows us “telephots” (video phones), but the conversations held over them are all trivial. There’s entire newspapers held on a single sheet of paper (you view different “pages” by exposing the sheet to different lights), and tube tunnels that take you right through the center of the earth, and gyroscopes that take you to Mars, and many other things, all described with breathless, autistic zeal.

But there’s a old-fashioned quality to Gernsback’s futurism. One of the arguments brought up against alien abductions is that descriptions of alien spacecraft always seem to track mankind’s cultural aesthetics (fifty years ago the interiors were all paneled wood and bakelite, now they look like something from the X Files), and Ralph 124C 41+ is like that. A futuristic society where you still have a manservant to bring you breakfast.

Despite the clever and evocative title, (“One to forsee for many”), the prose is very bad. Dangling participles scream from the pages. Gernsback doesn’t use many commas, and untangling his clauses is a constant headacge. This aside, the book has a graceless way of just…telling you stuff. Blurting it out. Here’s where we meet Ralph:

“He yawned and stretched himself to his full height, revealing a physique much larger than that of the average man of his times and approaching that of the huge Martians. His physical superiority, however, was as nothing compared to his gigantic mind. He was Ralph 124C 41 +, one of the greatest living scientists and one of the ten men on the whole planet Earth permitted to use the Plus sign after his name.”

A modern writer would communicate this by indirect means (perhaps Ralph has to stoop to get through the doorway after coming home from an award ceremony). Gernsback just cuts right too it. “Meet Ralph, he’s big, he’s smart.” Gernsback was a man of technical inclination, a builder of wireless radios and many other thiings (Ralph 124C41+ was first serialised in an electronics magazine), and he might have not seen the point of “show, don’t tell”. An electrical manual must provide exact specifications of capacitance and resistance, not just a demonstration of the device in action, and he probably took the same lesson to his fiction. He didn’t realise that fiction doesn’t traffic in information, it traffics in experience, and it’s hard to get any experience from overly-literal descriptions beyond “online dating profile.”

I was bored, and didn’t finish it. I guess this is the closest you can get to being ripped off by Gernsback in 2016, so that’s something. It’s like a cultural experience where you visit a reconstructed medieval village and they put you in the stocks for a few seconds or something. The book tries to take you to the future, but the lanes are crossed, and you end up stuck in the past.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.