It’s risky to form an opinion behind a curtain. Sometimes the curtain lifts, and you discover that you’ve picked a fight with the entire world.

For example, I have a friend who purchased a certain Atari 2600 game in 1982. It had an alien on the cover. From the above clues (and my tone) you might be able to guess the game he bought. This happened around Christmas, if that narrows it down further.

He didn’t like the game. It was arcane and frustrating; he wasn’t even sure of what he was supposed to do, and he spent half the time falling into holes he couldn’t see. It had glimmers of creativity, but it was also a confusing pointless headache. He returned the cartridge to the store.

Two decades later, he heard people on the internet talk about that game. First a couple, then hundreds. They hated it. It was seen as mythologically awful. Many of these people had obviously never played it—their descriptions were littered with factual errors—and they didn’t even want to. It was a fetish object to them: a thing to hate. As its legend grew, the criticism became ever scathing. It was the worst game for the Atari 2600. No, the worst game ever, full stop! The worst thing!

Huh, my friend thought. It wasn’t that bad. More annoying than anything. Loads of worse games on the 2600.

The question is…was he wrong? Or was everyone else?

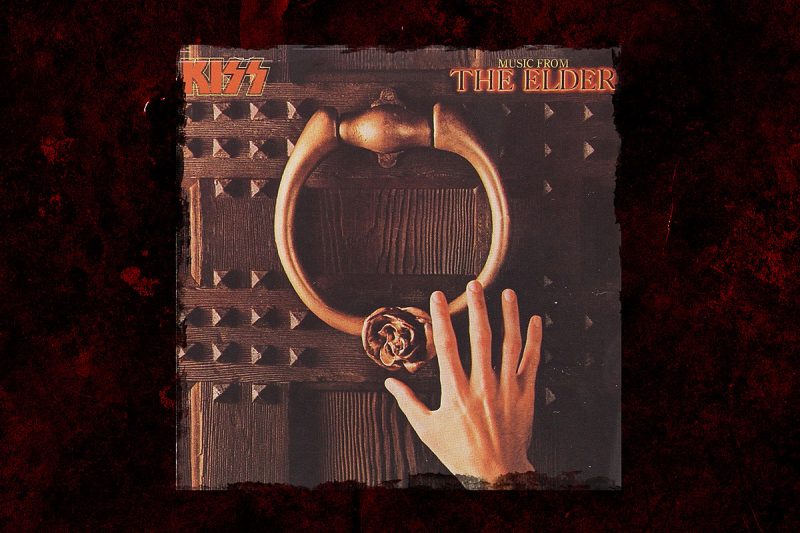

Music from “The Elder” is KISS’s version of the Atari E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial game. It’s remembered as the worst thing they ever did—their St Anger, their Ishtar, their Microsoft Zune. Its own producer has compared it to Springtime for Hitler.

I think it’s good. Turns out I’m in disagreement with everyone there, even KISS themselves. Oh well. Gene Simmons can bite me. His album’s good.

Most of the criticism The Elder receives is well out of proportion to its crimes. Yes, it has some bad songs. KISS has released albums that are uninterrupted shit from end to end, so I can live with that. Yes, it’s cartoonish in places, and the “story” makes no sense, and Paul sings in falsetto. But if you’re allergic to kitsch and are spinning KISS records, then I don’t know what to tell you.

The Elder is heavy and catchy and intricate. It shows a band trying to evolve their sound and do something new. More than anything, it’s brave. KISS was a shock and an affront, but how shocking are you being on your twentieth LP of party anthems? You might not like it, but “The Elder” is what peak shock rock looks like. I respect the hell out of it.

It’s “Bob Ezrin: The Album”. KISS was floundering in 1981: with their sales collapsing and their drummer vanishing out the exit chute, they reunited with the legendary Destroyer producer in the hopes of getting their career back on track. Unfortunately, Ezrin was high on the success of Pink Floyd’s The Wall—

(and on cocaine—let’s get that out up front)

—and he decided that only one thing could save KISS from certain death: a concept album.

As a band, KISS can be decoded in many ways. One of the most useful is “the Beatles with pyrotechnics and makeup”. Right from the start, they wanted to be the Fabber Four (Simmons often cites seeing The Beatles on Ed Sullivan as the hearing-Elvis-on-the-radio epiphany that spurred him to become a musician), and many of their questionable decisions are explained by “Paul and John did it”. The late-70s glut of KISS merchandise was no different to what Brian Epstein did for the Beatles a decade earlier, Kiss Meets the Phantom of the Park was a stab making their own A Hard Day’s Night, and when Ezrin decreed that the hour was nigh for KISS’s version of Sgt Pepper, how could Simmons and Stanley refuse?

Simmons came up with an exceptionally cruddy fantasy story, which Russell and Jeffrey Marks rewrote into a 130-page script that everyone knew would never be filmed. KISS superfan Brian Brewer bought the script at auction in 2000, and shares some details about the plot:

If you’re going describe this particular story it’s kind of on the same level as “Through The Looking Glass” [by Lewis Carroll, “Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland”]. It starts off in one era of time and you’ve got Blackwell, who’s the king and chief bad guy, and his henchman Xyte, who was actually a sorcerer for the Elders before he picked up with Blackwell. Blackwell is under attack when the script opens. The story starts with Blackwell under attack in his day, which is apparently 600 years in the past. There are allusions to a varying number of years in the script — one says 600, one says 800, one says 500 — they jump around, but on an average it seems to have been set about 600 years in the past. Xyte created another world inside Blackwell’s mirror chamber with the rose, which was a ring that the Elders created with magical powers and…

Actually, let’s just pretend there is no story and discuss the music.

The album is split between heavy rockers, conceptual pieces, and soft stuff. Ezrin is a pretty overwhelming creative force on here (along with Lou Reed), and the music is full of his signature touches—like that muted electrocardiogram bassline on “A World Without Heroes”.

“Fanfare”/”Just a Boy” throws KISS fans into the deep end. This is flowery twelve-string guitar stuff that sounds more like Renaissance Faire filk than hard rock. “Odyssey” is a torpid progressive piece with strange-sounding vocals from Paul Stanley. He seems to be trying to growl like Louis Armstrong in “What a Wonderful World”. It’s an okay song, but the key is clearly wrong for him. I wonder why Ezrin (normally a consummate perfectionist) didn’t insist that deep-voiced Simmons handle the track.

“Only You” has a powerful chorus riff, as heavy and twisted as a writhing serpent, and “Under the Rose” is a tricksy 6/8 prog-rock tune. “Dark Light” is the first uptempo song, with some ad-libbed asides from Ace Frehley. He barely seems to give a fuck, and it’s wonderful. Frehley apparently hated “The Elder” from the jump, and refused to even be present for many of the sessions. Needless to say, much of the lead guitar he’s credited for was actually performed by someone else (though honestly, it’d be faster to list the “classic” KISS albums where some form of that doesn’t happen!).

The Stanley-penned ballad “A World Without Heroes” was a bad choice for lead single, but it’s a fabulous song in the context of the album, with petal-delicate strings and one of Simmons’ most emotional performances. “The Oath” turns the intensity dial to 11 and then rips it off, with crushing NWOBHM-style riffs and wild drumming from Eric Carr—am I hearing power-metal style double-bass in 1981?

The album’s nadir is the Simmons/Reed composition “Mr Blackwell”, which is slow, club-footed, and lacks any sort of hook. Apparently Mr Blackwell was meant to be the villain of the piece: a “Washington D.C. power broker” who seeks global domination or something (note that the lyrics describe him drinking alcohol, which is the mark of Cain in Simmons’ world). The song’s just an absolute stinker, and derails the momentum of “The Oath”. At least there’s the Ace Frehley instrumental “Escape from the Island” to wake you up afterward.

There’s one song left. Gene Simmons, who has been a muted presence until now, stirs to life and delivers “I”, possibly the album standout. It’s an energetic, furious rocker, full of fire and heart. The lyrics could be applied to the story’s character, but could also be a dig at Ace Frehley (“Don’t need to get wasted / It only holds me down”) who, by this point, was eyeing the exit door himself.

I’m not really a KISS guy, truth be told. I like Destroyer well enough, and usually a few songs on each of their albums. But much of their party-hearty shlock just bounces off me: it feels like a dumber American take on what British glam rock managed with far more simplicity and purity five years earlier. But maybe that’s why I respond to Music from “The Elder”. For better or for worse, it’s the album where KISS is least themselves. “The mind was dreaming. The world was its dream.”

If this is a basic bitch album to like, call me a pH 14 female dog, because it’s actually great. Firm handshakes all around!

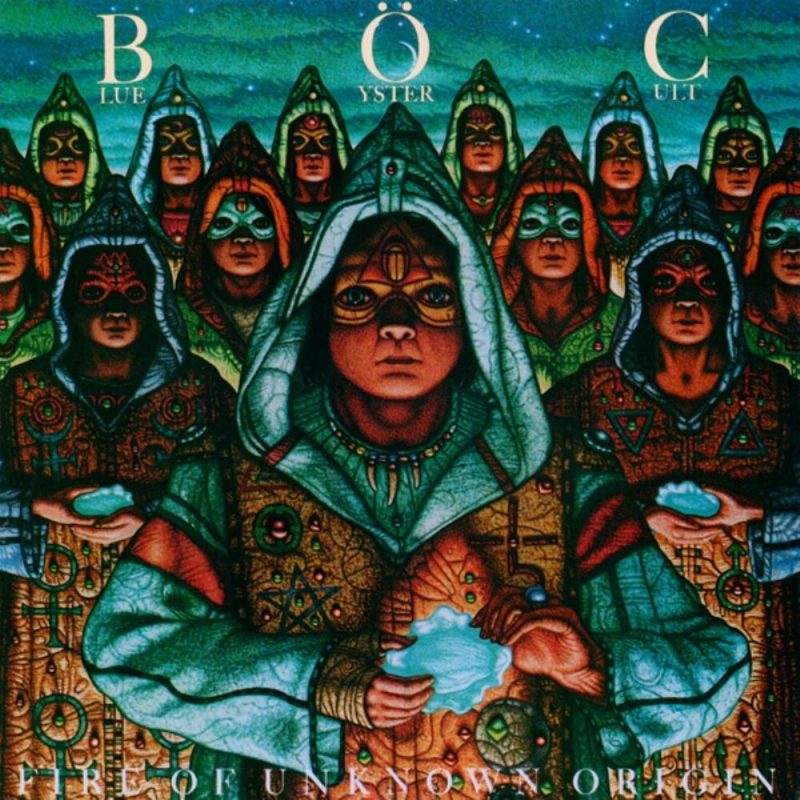

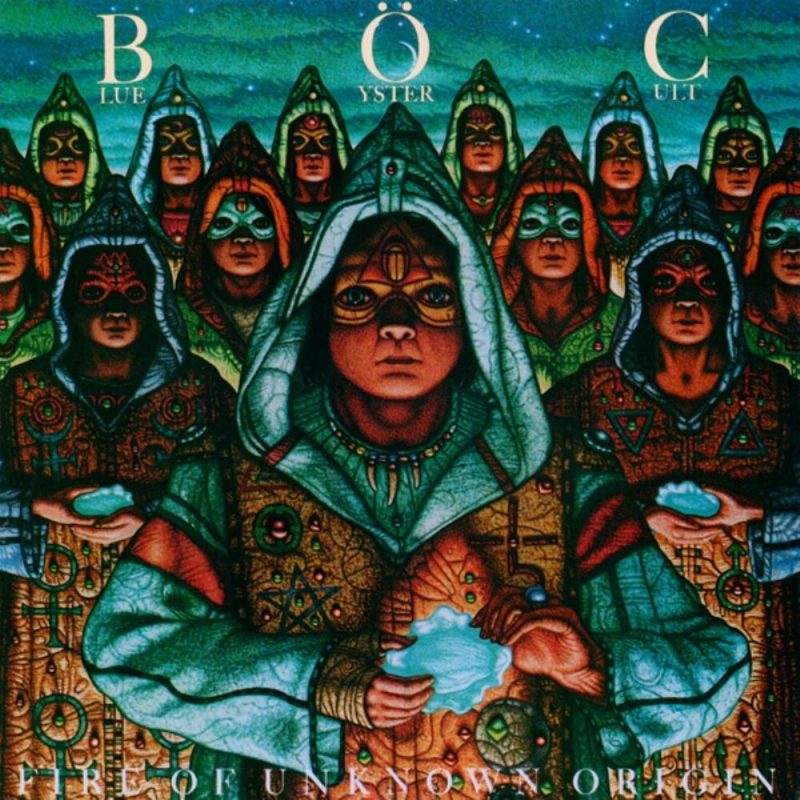

BÖC’s big “eighties” record achieves something remarkable: it combines the good aspects of several genres while avoiding all of their bad parts. Want heavy metal with no lumbering stupidity? Want progressive rock that’s catchy, immediate, and engaging? Want pop music that isn’t shallow? They do it all. The songs are excellently constructed, well-produced, and as compulsively relistenable as your phone banking password read out by an Indian man with a lisp.

Good songs:

The title track: simple and stately. It sets the stage, carving out the space that BÖC intend to explore (synths, guitars, new wave, NWOBHM). The keyboard presence has been greatly increased since their last album, matching the guitars in cut and heft, and J Bouchard offers a walking bassline that acts as the song’s heartbeat.

“Heavy Metal: The Black and Silver”: a big goofy Manowar kind of track. Presumably it’s one of the ones written and rejected for the Heavy Metal movie soundtrack, but BÖC usually have a song or two like this on every album (“Cities on Flame with Rock and Roll”, etc), where they play into the “heavy metal parody” thing suggested by the umlaut in their name. Gloriously stupid, its Black Sabbath-inspired riffs are crushing, and the call-and-response bridge acts as an interesting counterpoint.

“Sole Survivor”: another Bloom-written piece. I like the keys in the chorus. It does sound a bit too close to “Veteren of the Psychic Wars”, which precedes it in the tracklisting. The intro makes me wonder if J Bouchard double-tracked bass for this song. If so, good on him for keeping it as tight as it is.

Great songs:

“After Dark” is a high-velocity rocker, similar to the material found on Cultus Erectus. Relentless. Dare I say that the chorus has some ska influence?

“Joan Crawford”. A big and anthemic peak near the end of side B, with Grand Guignol horror lyrics that separate from the rest of the album. The significance of Joan Crawford coming back to life is lost on me, but if Jewish carpenters can pull it off, I guess 1930s screwball comedy actresses can, too. Maybe BÖC related to the idea of a one-time hitmaker being relegated to obscurity by career mishaps and changing times…and then escaping her coffin. Either way, the song is musically in good order, ending on a fun little JS Bach reference.

“Don’t Turn Your Back” is constructed from layered, ambiguous chords. Is the song sinister? Happy? It teeters between tones, unwilling to commit itself to a single mood. It’s like that moment in twilight where you’re not sure whether it’s dark or light outside. For a band that relied so much on sledghammer heaviness, this is a clever and thoughtful album closer.

Incandescent songs:

“Burnin’ For You” is a goliath of a track, as good a single as they ever wrote. The song is remorselessly catchy yet loaded with complexity: little ideas swirl and eddy within the larger piece. Harmonized twin guitar leads; a quasi-motorik inspired rhythm similar to what the Cars would do, Buck Dharma’s wild shredding; and Sting-styled vocals. Nearly a perfect song.

“Veteren of the Psychic Wars”. AKA, “My name’s Harry Canyon. I drive a cab.” This is the song that Ivan Reitman finally featured on the 1981 film Heavy Metal. Co-written by Michael Moorcock, it has lyrics that could relate to the Vietnam War, the counterculture, or some fantasy scenario. It’s extremely heavy and epic: again, Manowar’s entire career condensed into one song. The keyboards are tastefully used, and the military-style snare fills shuffling in the chorus are great. “Wounds are all I’m made of!”

“Vengeance (The Pact)” is maybe the album highlight. Albert Bouchard delivers a fantastic synth-driven heavy metal song that sounds like Manilla Road with good singing. The tempo picks up in the bridge, entering a Steve Harris-style Iron Maiden gallop (Martin Birch had just finished with Killers before this, come to think of it, so maybe the similarity is more than accidental). If I had to bitch, the lyrics are a bit heavy-handed and expository, basically describing the plot of Heavy Metal‘s “Taarna” sequence beat for beat. I’m not surprised Reitman didn’t use it. Why score a film with music that literally tells you the plot? Moorcock’s more cryptic approach suits the band better.

BÖC were always a little mismarketed. Their “heavy metal” cred was largely tongue-in-cheek, and they never had the patience to stick with it for long. They were a smart, diverse, creative band, touched by a quintessential strangeness. Whatever made them special, this is basically the last chance to see it. After this, A Bouchard is fired, and the band began a rapid descent into the worst excesses of the 80s. BÖC made many albums after Fire of Unknown Origin, but it remains the oyster’s final great pearl.

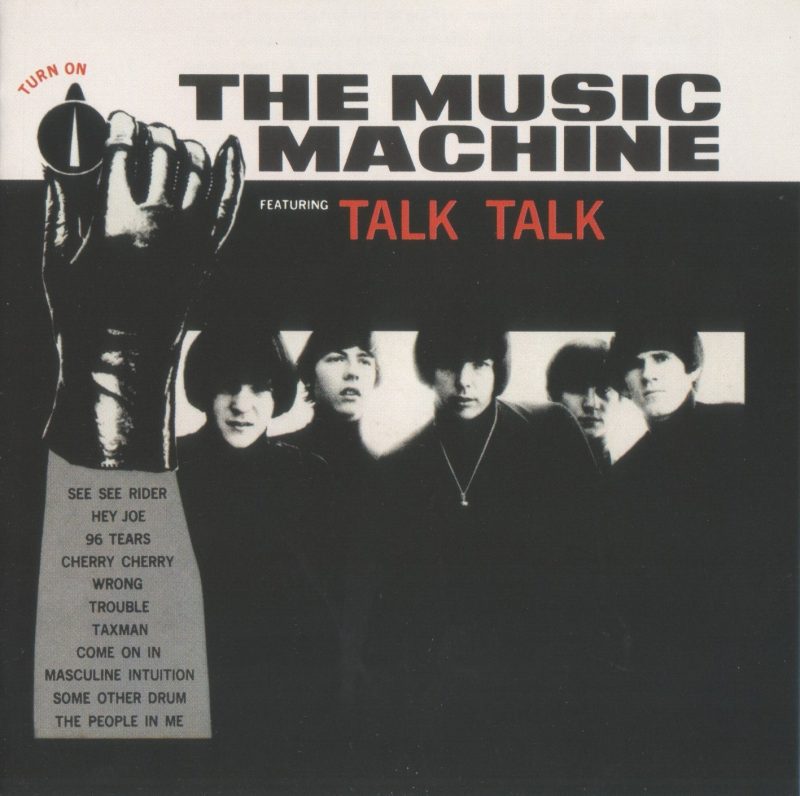

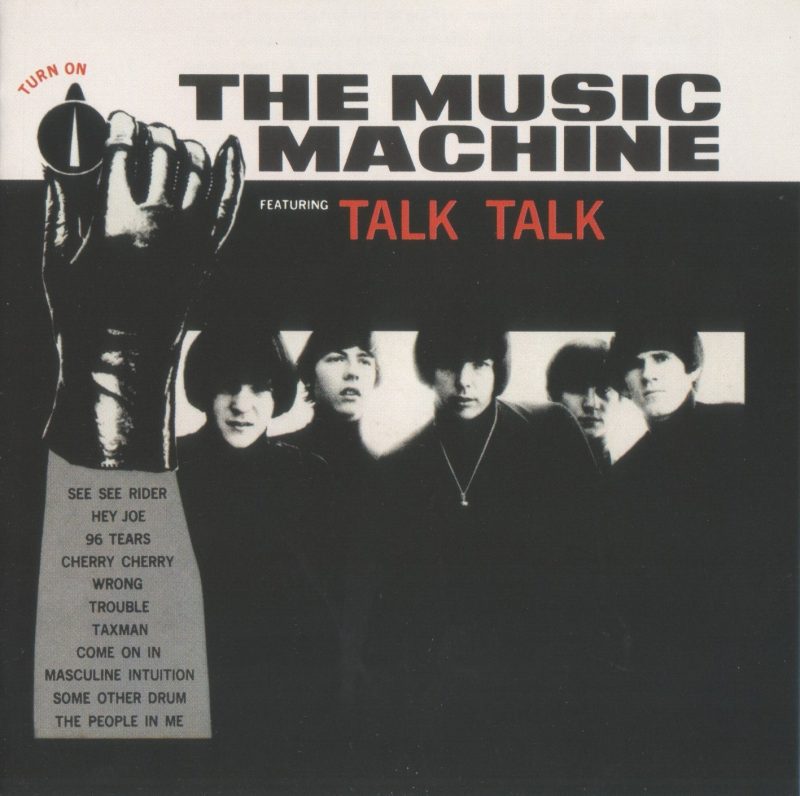

What did they think of “Talk Talk” in 1966? In 2023 it uncoils from your speakers like a cobra: alive and evil and glaring with death. It’s just 1:56 in length – short, even for the time. The tempo is punishing. The instrumentation is just lunges and stabs of fuzz; flames leaping from a barely-existent structure, as though the song’s burning down while still half-unwritten.

The lyrics are fragments. Ugly, mean thoughts, articulated with the stumbling self-seriousness of a teenager who’s drunk for the first time. “My social life’s a dud! My name is really mud!” Far from poetry…but people have thoughts like that. I used to. Sometimes eloquent phrasing doesn’t capture stupid, sullen emotions, “Talk Talk” may have been the first song they’d heard that truly sounded like the inside of their own mind.

The band was a five-piece called The Music Machine. One year earlier, they’d been playing folk rock.

They were fronted by Sean Bonniwell, a restless self-reinventor who never found a home. “Talk Talk”‘s success (#15 on the Billboard charts in 1966) proved a fluke. They had no followup hit. They were driven first aground and then apart by royalty fights, label disputes, and internal discord.

Bonniwell tried to regroup, but the window he’d exploited was now gone and his moment had passed. The Music Machine’s legacy is 1:56 of brutal noise and an unfulfilled promise. From the outside looking in, it was as though they’d come from nowhere and then gone back into nowhere. They did not become a Great Band.

But in a weird way, that helps me appreciate Music Machine more. There’s a long list of “classic” Rolling Stone approved acts (The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Queen) that I either can’t appreciate or appreciate in an academic thinking-things-through way. Part of it is their critical reception: they’re so adored and revered that it triggers suspicion in me. And it distances me from the music, I feel like I’m listening to it from across a GREAT BAND cordon line. The immediacy is gone.

Rock music was never supposed to be a canon, or an establishment. It was supposed to shake your bones. So I enjoy listening to bands like The Music Machine, that doesn’t have a Rolling Stone-appointed crown weighing it down.

If The Music Machine is remembered, it’s for either their heaviness, their earlyness, their subtle influence on other bands, or their rapid collapse. The entire band left soon after their first LP, aside from frontman Sean Bonniwell. He changed the band’s name, changed their style, and then left the music business altogether. It was as though the Music Machine had packed a thirty-year career into one minute and fifty-six seconds.

In other words, they were the Sex Pistols, ten years before. Which brings up the p-word.

Music journalism as we know it barely existed in the mid sixties: as a result, some history is barely-written and misremembered. A lot of people seem to think that punk rock was a seventies phenomenon. That was actually the second wave of punk. The first wave happened ten years earlier, with US “garage rock” bands like The Sonics and MC5, as well as UK acts such as The Downliners Sect and the Kinks. This was raw, aggressive, cheap-sounding music, driven by jangling guitars, powerful drums, and farfisa organs. Much of it was retroactively classified as “punk” in the early 70s – the first recorded reference to the genre is in the March 22, 1970 issue of The Chicago Tribune.

Unlike the second wave of punk (conspiracy theories about “God Save The Queen”‘s UK #2 aside), garage rock actually got some singles to number one. “”(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” by the Stones and “96 Tears” by ? and the Mysterians both reached #1, among others. It’s disputable to what extent these songs are punk. The lines between a garage rock band and, say, The Troggs or The Beatles could be pretty blurry. And their 1960s mod and greaser fashions have left less of an impression in the popular memory than the edgier styles pushed by Malcolm Mclaren and Vivienne Westwood.

The Music Machine were among the heavier of the 60s garage rock set, but soon psychedelic rock and heavy metal left them behind in sonic firepower, and Bonniwell proved unable to keep the band on the charts on the strength of his songs.

He was a clever and inventive songwriter, pulling inspiration out of the air, but maybe not actually a good one. “Talk Talk” is sonically impressive but soon wears thin. “Trouble” and “Wrong” are the best songs, particularly “Trouble”, with its dense and rubby rhythms and melodic complexity. “Masculine Intuition” has a really awkward chorus that doesn’t fit the verse. And it’s too short to develop its ideas much: all of these songs are sonic mayflys, dying before they can progress or go anywhere.

The album was recorded quickly to capitalize on a hit single. Most of the tracks were laid down at RCA Studios at three in the morning (on a hand-built ten-track machine built by engineer Paul Buff) after the band had been touring for thirty days, back to back, which explains Bonniwell’s hoarse, ragged voice. A surprising amount of punk aesthetic comes from what is ultimately accident and circumstance. Only in the aftermath does anything seem planned.

The band’s limited stock of originals is padded with covers, which are sometimes great (“Hey Joe” rivals Jimi Hendrix’s version. Bonniwell would later lament that his label wouldn’t release it as a single), sometimes pointless (“Taxman”), sometimes really stupid (“See See Rider”). The cover of “96 Tears” is pretty ironic, as ? and the Mysterians also failed to follow up their one hit.

The Music Machine is a fascinating curio, but they were riven by image and identity conflicts that they never figured out. Were they art, or yeah-yeah-yeah teenage music? They were initially presented as mods, but Bonniwell soon got into transcendental meditation and eastern mysticism. There was little sense of musical history to the Machine. You couldn’t obviously pick out their influences, the way you could for the Beatles or the Stones. This made them seem fresh, but also a little disconnected in time, as though they were visiting aliens. There wasn’t an easy “story” you could apply to the band, which made it easy for music history to not give them a story at all.