TekWar is the first in a series of cyberpunk novels “written” by William Shatner. If you read sci fi books around 1990, you’ll vaguely remember TekWar. You’ll vaguely remember it so damn hard.

According to popular legend, Shatner wrote the book during a strike on the set of Star Trek V. According to unpopular legend, it was the work of professional ghostwriter Ron Goulart. According to a bullshit lie I just made up, it was actually written by popular entertainer Herbert “Tiny Tim” Khaury while his ukelele was in the shop for repairs. Since truth lies in the middle, we can confidently say TekWar was written by Shatner, Goulart, and Tiny Tim working together and no I will not take further questions.

The book is about future-cop Jake Cardigan (far less cool than his brother, Jim Pullover). Framed for dealing a “Tek”, an illicit mind-altering drug, he must clear his name by infiltrating and cracking Tek cartels at the behest of a shadowy PI agency.

Today “cyberpunk” means a fluffy visual aesthetic, but in the 90s it meant a literary movement: Ballardian/Ellisonian “new wave” sci-fi with an emphasis on the sordid side of life: drug use, crime, and urban blight. Cyberpunk was raised around the principle that it’s not beauty that defines an age, it’s ugliness. The true face of the Middle Ages isn’t the Chartres Cathedral but the bubonic sores festering on a peasant’s neck. The 21st century will be remembered for World War II and the Holocaust, not the Green Revolution or the moon landing. As Hitler’s chief architect Albert Speer realized, ruin and death have a fetishistic compulsion that draws us in and forces us to stare. What will the future of decay look like? The verdigris yet to flower, the crack yet to appear? How can we depict that?

In practice, the average writer isn’t very imaginative, and most 90s cyberpunk stories feature a futuristic setting awkwardly bolted to a bog-standard 1950s crime/western plot (Gibson’s “console cowboy” trope is an unsubtle nod to this). They were quick to write and cheap to adapt to film (places like Hong Kong’s Walled City and New York’s East 14th Street looked fairly cyberpunkish without a dollar spent on set dressing), and this led to a glut of substandard work that crashed the market.

Next to the genre’s more interesting works, such as Vurt and Snow Crash, TekWar stands out as particularly disposable. ”I wrote them as the sort of books you could read on airplanes and throw away afterwards,” Shatner once said. With that kind of sales job, I bet you’re itching to read TekWar already. But I am not here to talk about the book, or the TV show, or the other TV show, or the movie, or the comic book, or the marital aid.

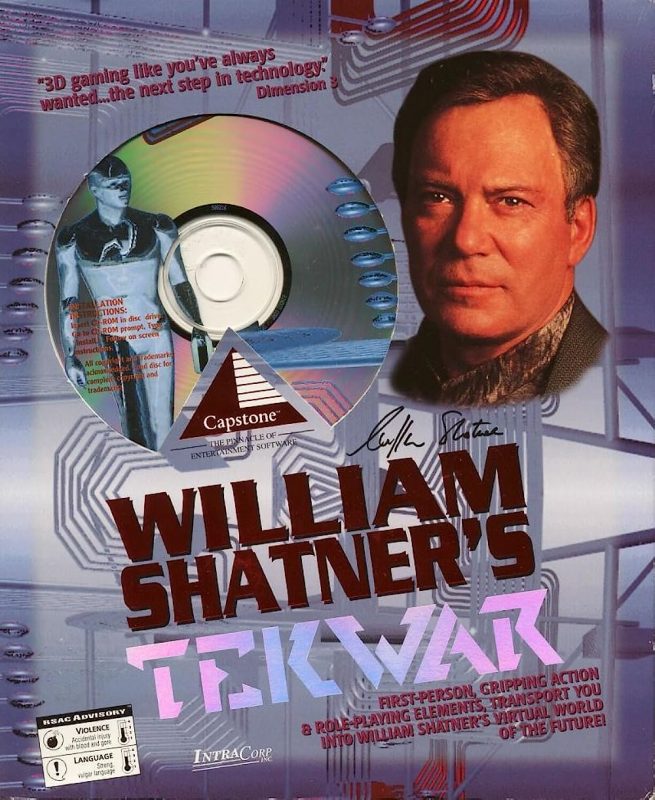

I am here to discuss the PC game.

TekWar was a first-person shooter that came out in 1995 and left no trace on popular culture. That’s because it is a bad game. But in the long run, it wouldn’t have mattered if it was good.

Games have the lifespan of mayflies: they are released, played by however many people play them, and then fall into the same abyss; goodnight. Where they fall to, we cannot say. There is no thud as they hit the bottom. I remember countless PC games that once stood above the market like titans: dominating, inescapable…and now they’re gone. They’re not even obsolete, it’s like they don’t exist. Nobody talks about them, few even remember them, and if you think you do, it’s actually your childhood your remembering, not the game. Don’t believe me? Try replaying your favorite childhood game. It will feel strange and awkward and totally unlike your memories: you’d swear the game has been sucked out of the timeline and switched with an inferior off-brand copy. Your childhood is gone. The door into adulthood swings one way.

Music isn’t like that. “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” is from 1968 and still sounds like it was recorded this morning. The #1 song on the UK pop charts in January 1991 had Gregorian chanting. Occasionally a random song from decades ago will go viral, racking up tens of millions of listens for no other reason than it’s good and people like it.

Music lives forever: the same is not true for videogames. The most they can hope for is that an embarrassing Youtuber called “PixelNostalgia” or “8BitMemories” will waddle through it in DOSBox to the adulation of two hundred viewers. I remember this game! It was so great! I played it when I was six! Again, it’s not about the game, it’s about their childhood. Old games have past tense constructions (was, did, had) hanging around them like flies around roadkill. Their moment is short and they never get a second one. No revival is scheduled for The Fortress of Dr Radiaki.

1995 was an awkward year for first-person shooters. The “pseudo-3D” technology that had railgunned 1993’s Doom into the stratosphere was beginning to age, but the 3D revolution of 1996’s Quake hadn’t arrived yet. The industry settled into a holding pattern: we got iterations on the Doom formula (Heretic/Hexen/Star Wars: Dark Forces), as well as noble experiments (Magic Carpet 2/Descent) that never really felt like finished games. Everyone seemed to be holding their breath.

Then came Ken Silverman’s Build engine.

Silverman was a child prodigy from Rhode Island with a savantlike grasp of graphics programming and assembly code. Around 1992, he saw his brother playing a new game called Wolfenstein 3D, thought “I could make that” and…uh, he did. He reverse-engineered John Carmack’s cutting-edge “3D” engine from scratch, without a peek at the source code. He was sixteen years old.

Doom caused a spike of interest in shooting games. Licensed engines became a hot commodity, and so did the programmers who could work with them. In 1993-4, Scott Miller of Apogee wanted to develop a 3D shooter, but id Software wouldn’t sell him the Doom engine, so he hired Silverman to write a copy of it.

What followed was a long, messy process (Silverman had just enrolled at Brown University, and was soon failing entry-level courses because he spent all his time programming!) that culminated in Build, an quirk-filled oddball engine that powered some of the most memorable games of the 90s.

Build wasn’t a visual feast. Essentially a 2.5D engine with a lot of fancy tricks, it looked good by 1994 standards, passable by 1995 standards, and was severely manhandled by Quake. It was clunky and awkward. Everything cool it could do—such as rooms on top of rooms and mouselook—was achieved through an ugly hack. Silverman was a self-taught programmer, with all that implies, and his code was notoriously abstruse and buggy. This caused frustration for the programmers who had to work in it. I watched someone “speedrun” Duke Nukem 3D: it was actually kind of funny. He barely played the game, he simply exploited one glitch after another, clipping his way through whole levels.

So where did the Build engine shine? Dynamism. It did stuff. Unlike Doom‘s idTech 1 engine, which relied on pre-rendered BSP trees, Build generated level architecture on the fly, meaning walls and floors could move, rotate, and shift. Build took those little moments of environmental interaction in Doom (such as crushing a Spider Mastermind beneath a descending ceiling) and amplified them by a factor of ten. 1996’s Duke Nukem 3D let the player launch nuclear missiles and blow entire landscapes to pieces. 1997’s Blood had a level set on a moving train. 1997’s Shadow Warrior had driveable vehicles years before Halo. Few engines have been so exhuberantly designer-focused as Build.

The earliest Build game to exist (for a relaxed definition of “exist”) was 1994’s Rock’n Shaolin: Legend of the Seven Paladins 3D. It was the illegal afterbirth of a failed deal between Apogee/3D Realms and a Taiwanese/HK studio called Accend. For years, it was believed that the game was never finished (although Accend did leak an unauthorized demo on the internet), until someone found and photographed a game box at a flea market. So apparently Accend actually finished the game? And then released it, in complete defiance of the law? But didn’t advertise or promote it at all? I don’t know. There’s a lot of weird rumors surrounding that game. It’s cursed, and we’ll talk no more of it.

The first legal Build engine game was 1995’s Witchaven, a graphically ugly and technologically primitive Heretic-clone that I will probably never play again. I have made peace with that fact.

Witchaven is the most drab and depressing-looking game I’ve ever seen. The enemies look like claymation trolls melted with a hair-dryer. The controls suck. Combat consists of lining yourself up with enemies and swinging a melee weapon at them—which is frustrating, because there’s a delay of about a second before damage registers, and the first-person perspective means you can’t see where your feet are. Your melee weapons break after a few swings. At times Witchaven seems hell-bent on denying the player any sort of fun. The designers exploit virtually none of the Build engine’s possibilities. If the story of Build had ended with Witchaven, the engine would be forgotten today.

But then Duke Nukem 3D came out: a wonderful romp packed with style, personality, and humor. Quake was a leap forward for 3D technology,but Duke 3D was a comparable leap for design. It’s packed with silly cosmetic touches—you can flush toilets, and roll balls around on a billiards table—that individually seem pointless, but when you have a thousand of them the game just sparkles to life. When you played Duke, you felt the winds of change blow. The “boomer shooter” era of space marines shooting aliens in gray metal corridors was drawing to a close. Blood and Shadow Warriors (two more Build Engine games) further sealed the deal: shooter games could and should depict a living, breathing world.

But between Witchaven and Duke Nukem 3D, we got TekWar.

Again, we have Capstone Software to thank. I don’t know if this was made by the same team that worked on Witchaven. Given the differences in art and style, I guess would guess at “different people”. A sufficiently motivated writer would check the credits on MobyGames. I am not that writer.

TekWar features an early-gen version of Build, scarcely more capable than the version under the hood of Legend of the Seven Paladins. There are no slopes, rooms-above-rooms, or voxels. It supports reflective surfaces, but when you see yourself in a mirror you’ll wish it didn’t. Your character has no animation, and slides around as if on roller-skates.

TekWar loosely adapts the book’s story. The detective (deTektive?) elements are gone. Now Jake Cardigan is a wet-worker hired by Walter Bascom (voiced by William Shatner) to murder Tek dealers on the street without a trial. Who am I working for? Rodrigo Dutuerte?

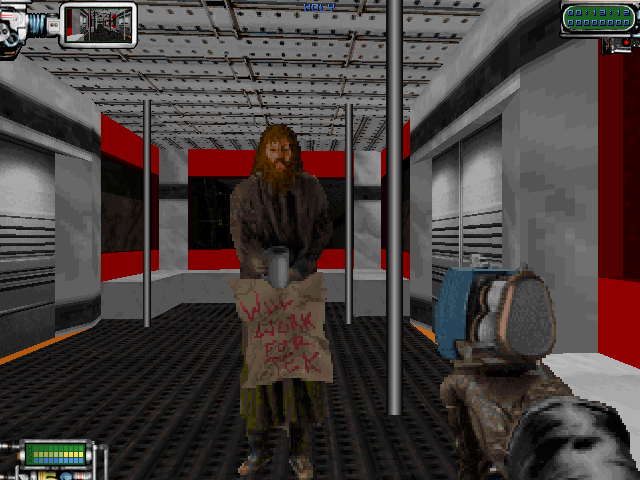

You walk around city streets with your gun awkwardly jutting into the field of view like you’re a flasher with your dick clenched in your hand, looking for Tekgoons. It’s embarrassing. This could have been a setup for another brainless Doom clone, but TekWar is actually strangely creative. It boasts an intriguing “open world” layout: instead of playing levels by tapping through a menu, you step on a train inside the game, which takes you to part of the city controlled by one of the seven “TekLords”. This train station acts as a central hub, keeping you inside the experience and adding to the sense of immersion. This is standard today, but the idea of taking a train in a videogame seemed cool in 1995.

TekWar has sparks of the still-uninvented “tactical shooter” genre. The game is populated by NPCs who bumble around and get in the way. Shoot at them, and police start attacking in waves. This (in theory) forces you to be smart: rather than killing everything that breathes, you must eliminate Tek dealers while sparing civilians unharmed. Doom is “you against the world”. TekWar is “you against team 1, while trying to pacify team 2 by not hurting team 3”. This idea, if it had been done well, would have added a tactical, cerebral edge to Tekwar unlike any FPS game yet to be released. It would have been a revolution.

It’s not done well. The AI is Daikatana-level terrible, and this makes it impossible to plan or predict what will happen. Cops ignore Tek dealers who are firing guns at you, but the moment you unholster a gun to fight back, the cops start blasting away at you too. It sucks.

Everyone in this game is absurdly sensitive to sound. You can unholster a gun in an empty room and hear cops reacting to it in the street outside. Often it’s quicker to just massacre everyone you see, cops and civvies and bad guys alike, and deal with William Shatner’s bitching afterward. Better to be tried by twelve than carried by six.

Even if you’re a boy scout who’s dedicated to minimizing casualties, it’s easy to shoot civilians by mistake, because they look like enemies, particularly at a distance. The enemies themselves are identikit clones: I accidentally killed a TekLord (!) and didn’t even realize it until Shatner started congratulating me. I assumed he was just a regular enemy who was soaking up a lot of my shots for some reason, possibly because the game’s hit registration is terrible.

Tekwar has severe Teknical difficulties. Bugs I’ve seen or heard of include:

- You sometimes lose all your weapons when starting a new level.

- If you get pinched between two sliding doors, it kicks you back to DOS with an “INVALID SECTOR FOR PLAYER” message.

- Like Doom, enemies can be “gibbed” by explosions. However, gibbed enemies don’t drop vital keys, and levels become unwinnable if this happens.

- Binding movement keys to your mouse allows for super fast movement for some reason.

Some glitches are honestly adorable. In the Carlyle Rossi section of a game, there’s a ceiling-mounted turret that…isn’t a turret. It moves around the ceiling, chasing you like a lost dog. (An explanation for this I found on a forum: the turrets are considered regular enemies in the game code, just with their movement speed set to “zero”. But this parameter had to be set by hand, and the developers evidently forgot in the case of this one turret. So it moves.)

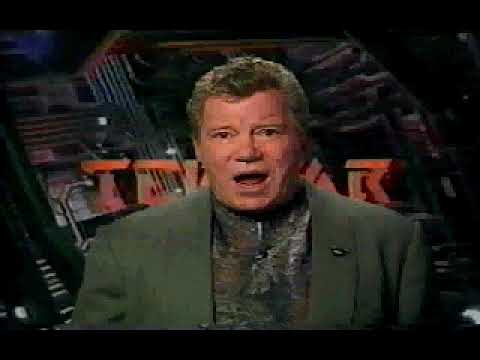

The game has FMV videos, where your boss Walter Bascom (played by William Shatner) gives missing briefings. He’ll say stuff like “Quick! I’m uptown, and I just saw Marty Dollar! Get down here and help me bring him in!”, giving the impression that the game’s is co-op and you’ll be fighting side by side with Captain Kirk. And do you? Don’t be stupid. Shatner never once appears in the game.

I should mention that 1995 was also the peak of the “interactive movie” fad, when people thought the future of gaming lay in clicking buttons and watching 320×240 Smacker files of actors reacting to what you just did. If you eliminate a TekLord without harming civilians, Shatner praises you. If you fail in either of these tasks, he yells at you (although I’ve found that he sometimes compliments you on a bloodless victory when actually you did kill a civilian. Maybe it was a minority.)

I enjoy Shatner as an actor, but I don’t need to: nobody loves him as much as he loves himself. His every line is delivered with consummate smugness. “I’m not gonna waste your time…or, more importantly, my time.” And then he pauses for an uncomfortable amount of time so you can chuckle. And it’s 1995, so the videos all look like this.

If you’re allergic to excessive pixels, don’t worry, these videos won’t even trigger a sneeze. The actual game is at leats more colorful than Witchaven, but in a garish, kitsch way, with a color palette ruthlessly optimized for ugliness. The in-game sprites are rotoscoped from real-life actors (probably from the TV show), which sounds great in theory, but creates a persistant sense of unreality. They clearly do not belong in the world of the game.

Do you see what I mean? The actress is being lit from her right (camera left), but there’s nothing in the game that could be casting that light. She’s standing next to a building, and should be in shadow! This sends a white-hot signal to your brain that something’s not right. Every character model has the same problem: they are illuminated and highlighted in all the wrong places, and it breaks the illusion of reality.

Other Build engine games dodged the problem by rendering sprites in very soft light (Duke 3D, Blood), or by being so cartoony that it didn’t matter (the rest of them, basically). Tekwar, with its Promethean striving for realism, actually looks the fakest out of any of them. It doesn’t help that the sprites often have really shitty roto, with bits of the backdrop visible on their models.

Everywhere you look, the reality of the game world is broken by sloppy and bizarre touches. The textures don’t match up. There’s water, but you can’t swim: you just instantly fall to the bottom and then start walking again (amidst reeds that don’t seem to connect with the floor). Climbing ladders is absurdly slow. This is the only game I’ve played where it takes longer to climb a ladder than it would have taken me in real life.

Then there’s the infamous “matrix” levels, which are totally confusing, are ripped off from System Shock, and just look like complete ass. Nothing makes visual sense. If anything, it looks like one of those “filler” games from Action 52, where it’s just a jumble of random sprites they had lying around. And that’s basically the climactic ending point of the game.

So, in TekWar we find some ambitious ideas, along with execution so botched that not even the combined powers of Capstone, Will Shatner, Ron Goulart, and Ken Silverman could save it. I wish I liked it more, but Tekwar badly needs teknical support.